Images: Portrait. Elmo Henry Brown, paternal grandfather. unknown date. San Antonio, Texas. Portrait studio (unknown). Phyllis Zumwalt’s private collection.

Searching for death records and other details about our ancestors’ demise may seem morbid, but the analysis may provide a helpful view into familial, hereditary conditions and the diseases our ancestors encountered. Death certificates in the United States became more common in the early 20th century, as a way for public health officials to track and study deaths among populations. For genealogists, these documents oftentimes present clues not easily found (like parents’ names, residence, funeral home (for further research), burial location or cremation, and of course, date of death, age, marital status, and cause of death). To discover when a particular state implemented civil death certificates, check this “Where to Write for Vital Records” website by state.

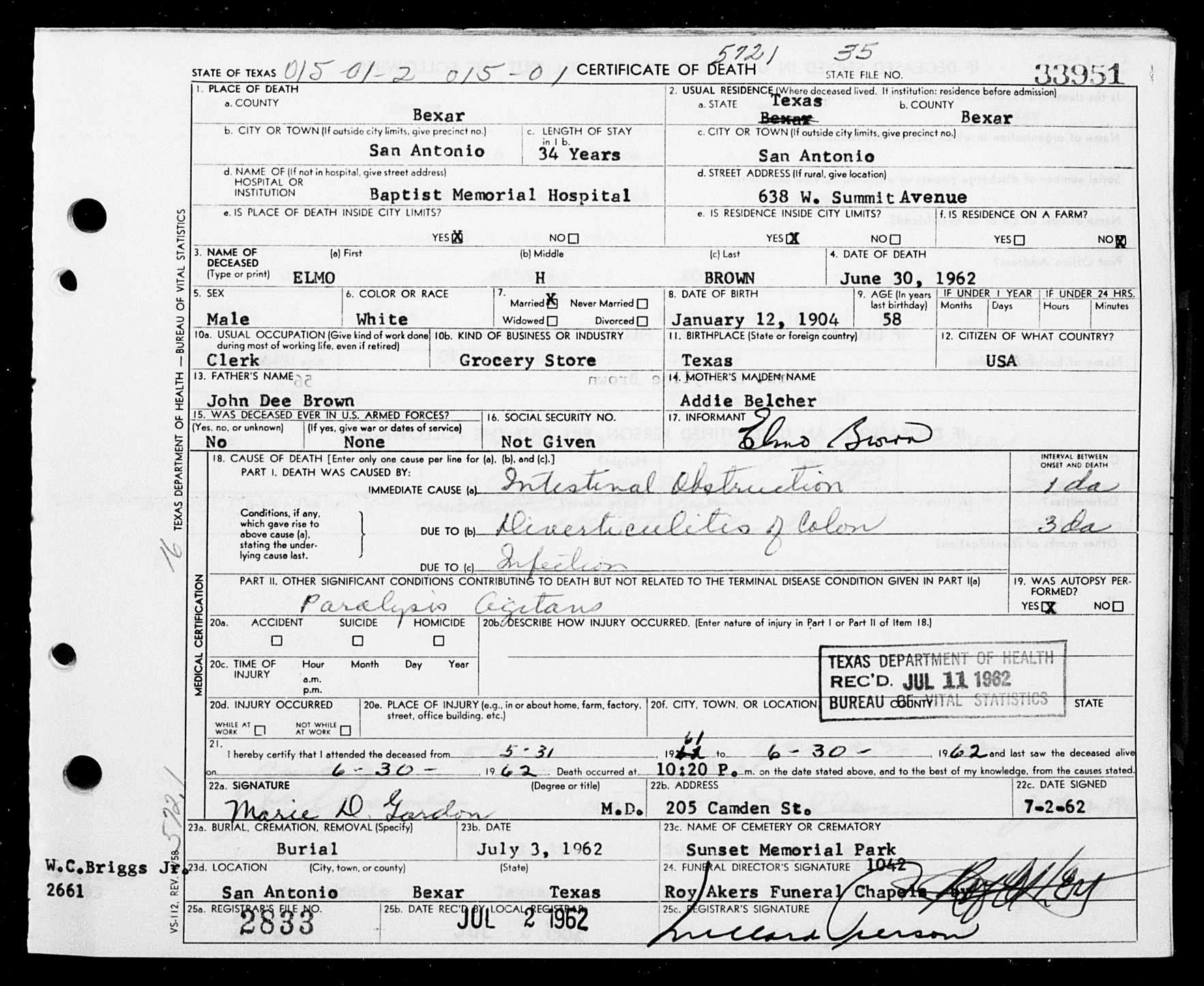

In my paternal line in Texas, there was a short history of intestinal issues; colon obstruction for my grandfather (died at age 58, as noted in the death certificate, below) and colon cancer (my father, who also died at age 58). The majority of the men in my paternal side of the family lived to be in their 80’s and 90’s, dying of heart disease or senility (also described as “old age”). The women on the paternal side of the family, also in Texas, died from cerebral hemorrhages (strokes) or heart disease, most also living into their 80s.

A further detail in the death certificate (below) of my paternal grandfather, Elmo Henry Brown, was that he had an underlying condition, “paralysis agitans” commonly known as Parkinson’s disease. His condition was documented as caused by a result of the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic. Causation of this nature were further studied, described well by the British Broadcasting Company (BBC) in their article, “How past pandemics may have triggered rising cases of Parkinson’s.” As a side, this article shared that scientists and doctors are concerned about how the recent COVID pandemic may contribute to similar neurological conditions in future years; possibly another underlying “significant condition contributing to death not related to the terminal disease condition” that genealogists will be researching for years to come. My father, Elmo Brown, signed the death certificate of his father.

Texas. State Registrar Office, “Texas Deaths, 1890-1976,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K7DD-G7Q : accessed 25 November 2024), certificate image 2518 of 3498 for Elmo H Brown, 30 June 1962, state file no. 33951; citing, Texas State Registrar Office, Austin.

- a suicide (at age 21, shortly after the gentleman married amid financial debts, 1912)

- typhoid fever (a gentleman who was 21, had caught the disease and died in 1936)

- tuberculosis (a gentleman who was 36 when he died in 1921)

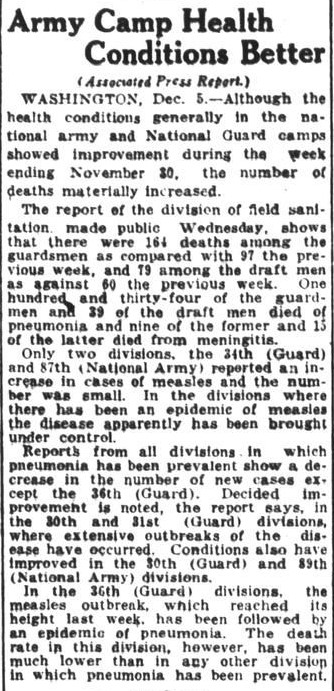

In addition, there were many other highly contagious diseases like measles (which can lead to pneumonia), mumps, rubella, small pox, diphtheria, polio, and more which affected hundreds of people at a time and caused many deaths. To learn more about a specific disease, search it and the word “outbreak” in newspapers. The culprit to starting these outbreaks were usually caused by travel (of those already sick) and occurring where people congregated; children in schools, people in church, and notably, soldiers in military training camps.

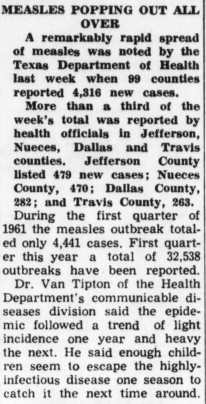

Example: Measles Outbreaks

Searching the Portal to Texas History (my favorite free resource in Texas) for “measles outbreak”, as an example, resulted in 300 results. As a youngster in the early 1960s who had measles and then mumps (before there were vaccines), I was curious to see what news I could find. As noted in the first image for 12 April 1962, measles in Texas had exploded in 1962 compared to the same time in 1961.

Measles usually did not cause deaths but there were cases where it would lead to pneumonia and those who were most vulnerable would succumb. The second image reflected the epidemic created in 1917 when soldiers attended training camps in preparation for deployment to the front lines during World War I.

Austin Highlights, “Measles Popping Out All Over,” The Hereford Brand (Hereford, Texas), 12 April 1962, p. 16, col. e; image copy, The Portal to Texas History (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth1239498/m1/16/ : accessed 25 November 2024), Texas Digital Newspaper Program.

Associated Press Report, “Army Camp Health Conditions Better,” The Houston Post (Houston, Texas), 6 December 1917, p. 2, col. b; image copy, The Portal to Texas History (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth609041/ : accessed 25 November 2024), Texas Digital Newspaper Program.

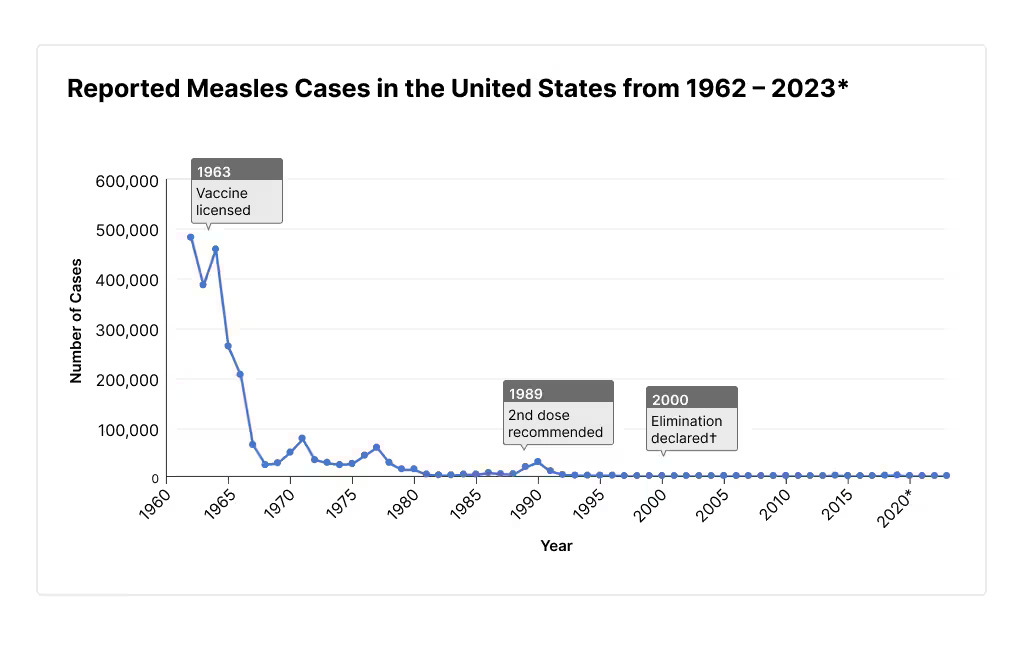

As noted on the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) website and visible in the graph below, a vaccine was licensed in 1963, but the vaccine evolved over time to become a two-dose regimen. See the History of Measles to learn more, and why it continues to exist in the United States. Use the CDC’s search function to see other diseases, their data and histories.

When searching again in the Portal to Texas History for “measles vaccine“, there were over 1200 instances. Searching the 1960s decade, there were 25 newspapers instances in 1963. Most of the articles focused on how the government worked to license and distribute the vaccine before the winter months, when the disease was most prevalent. A comparison to the polio vaccine was noted in some newspapers, acknowledging that the polio vaccine was quickly deployed; the contagious nature of that disease required a fast solution.

Example: Poliomyelitis (polio) Outbreaks

The United States implemented the polio vaccine in the 1950s, effectively reducing the risk of contracting it. See this brief concerning the CDC’s mission to assist in eradicating it globally at a cost of 10 cents per dose. When researching deaths, it is important to understand the history of the ailment which helps to understand the struggles the family might have had to endure. Many families in the 19th century had numerous children, as a help for farming, but also because so many children died before the age of five. To learn more about a particular ailment, search public health sites like the CDC, local county offices where the ancestor died, or through historical books, diaries, and journals.

Searching the Portal to Texas History for “polio outbreak” resulted in 576 instances, with the majority in the 1940-49 and 1950-59 decades. Deeper analysis showed many headlines and additional articles which described “clean-up activities” with spraying of residential neighborhoods, trash pickups, and other efforts to allay the spread of that disease. One article stated that the disease came in 3-year cycles which must have spread fear through communities. The CDC promotes World Polio Day, observed October 24th, which highlighted it as “the most feared global health threats, causing illness, paralysis and other disabilities, and death in both children and adults around the world”.

As noted above, funeral homes and cemeteries (if large and well-established) sometimes had notes about their clients. Most of my paternal line migrated from Georgia to Nacogdoches County, Texas before 1860. I discovered a fabulous resource provided by Cason-Monk Funeral Home in the city of Nacogdoches, to the East Texas Digital Archives; their funeral registers (25 of them!) from 1900-1957. My great-grandaunt, Leta Belser Martin (my paternal great-grandmother’s sister) died 4 September 1900 of “conjestion / chill” (now commonly known as pneumonia); see page 3 of the 1900-1911 register. These deaths were listed in chronological order so it is relatively easy to discern when an outbreak took place. Scanning through several pages you can see that conjestion (pneumonia), consumption (tuberculosis), and fever (typhoid fever) were the most prevalent, hitting many people in their 20s and younger. The latter part of the year 1900 in the Nacogdoches County area was a disease-ridden time.

While her FindAGrave entry did not reveal any biographical details, an infant sister’s FindAGrave biography revealed that she was a twin (to a sister, Jewel), a key piece of information if not already known.

Remember – searching for death records for your ancestor may reveal interesting details, particularly in historical context regarding the diseases and illnesses frequently experienced prior to modern medical advances (vaccines, treatments, other preventative measures).

Note: Make sure your children know your family history! In addition to sharing with them about the “good, ole days”, ask them to record you or have you share / write down the details of your life and lineage. See the blogs about using a research plan and conducting interviews, in the Research Services category.

If you have any questions regarding the information in this blog, please reach out to me. You can also follow SYFT on Facebook, Instagram, Bluesky, or LinkedIn, fill out the Contact SYFT form, or email us directly at shapingyourfamilytree@gmail.com. Sign up for my newsletter to see deals on genealogy services and to stay current on genealogy events, news, and tips and techniques. Let’s share our experiences!