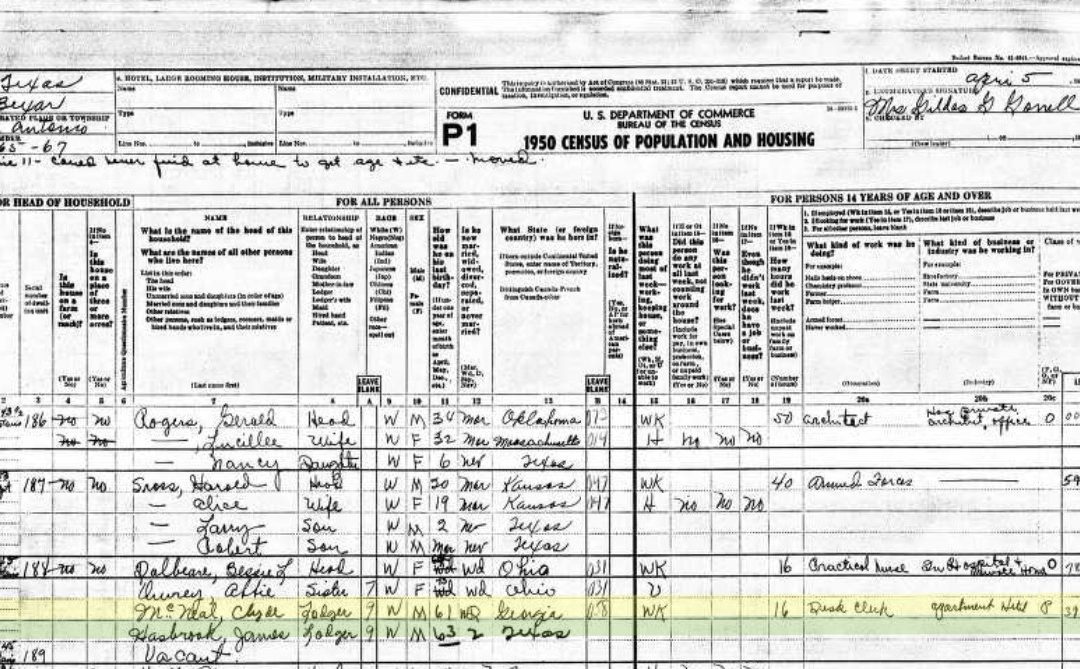

In our “Researching Online” series this week, we review how census records can help a researcher locate facts, provide depth to a family story, and even add (or remove) confusion as names may differ, ages might be false, and birth locations can conflict from one census to the next (based on informant’s knowledge). It is very important to understand the enumerator instructions and what their special marks and notes might mean. Finally, special non-population census records and reports (agriculture schedules, etc.) can reveal more information about an ancestor.

To understand how a researcher can use census records, The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (commonly called the National Archives) provides a nice introduction to using them, https://www.archives.gov/research/census/about. The National Archives maintains all historical census records online for the United States, from 1790 – 1950 (decennially, every ten years) and provides the links for partners who provide the data (Ancestry, FamilySearch, etc.).

For these years and through to 2020, the United States Census Bureau also has informative pages describing the details of census records, links to enumerator instructions and even lesson plans for teachers to use in teaching various topics. The Decennial Census Records webpage contains a summary; a good place to start, if you’re new to using them, https://www.census.gov/history/www/genealogy/decennial_census_records/. Another favorite website is “Through The Decades”, https://www.census.gov/history/www/through_the_decades/ contains facts, overviews, and instructions.

Non-population census records (agriculture, mortality, and social statistics schedules as well as 1935 Business Schedules) are described in more detail here, https://www.archives.gov/research/census/nonpopulation. Publications including genealogy, statistical analysis, demographics, economics, housing reports and more can be found here, https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/publications/.

If you encounter any issues using census records, I’m happy to talk through the conversations and offer advice. You can fill out the Contact Me! form or email me directly at info@shapingyourfamilytree.com.

Where can I find information for historical online Census Records?

| Census Year | National Archives | Census Bureau | Census Bureau PDFs |

| 1790 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1800 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1810 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1820 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1830 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1840 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1850 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1860 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1870 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1880 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1890* | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1900 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1910 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1920 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1930 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1940 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

| 1950 | FAQ | Fast Facts | Enumerator’s Instructions |

* Much of the 1890 U.S. Census data is missing due to a fire which destroyed most records; a gap of census data exists between 1880 and 1900. https://www.census.gov/history/www/genealogy/decennial_census_records/availability_of_1890_census.html.

Favorite Census Records:

Every genealogist has favorite record sets. In the case of Census Records, my favorite U.S. record sets are:

- 1900 Census, which has the month and year of birth and age for each person.

- 1910 Census, which asked of the mother, how many children did she have and at that time, how many were still alive. While a bit morbid, this data can be very useful for validation of children and their potential (early) deaths, especially at this period of the 20th century when diphtheria, typhoid fever, scarlet fever, consumption and whooping cough (and other diseases) were common (prior to vaccines).

- 1920 Census, when the census asked “if naturalized, year of naturalization.” This data is SO helpful when researching migration stories.

- 1930 Census, which asked a person’s age at the time of his or her first marriage.

- 1940 Census, which has a field for the individual’s residence in 1935.

- 1950 Census, as it was just released this past April!

Use census records with an air of caution. Many times the informant may not have known all of the data and just guessed, especially on birth locations. Often the enumerator was not fluent in the spelling of various names and may have written them phonetically. Some people did not give their correct age, especially women who were single or widowed.

Always look on pages before and after your ancestors’ record as families / friends and important acquaintances may have lived nearby. A recent client had ancestors with soon-to-be brides and grooms living nearby. Many people lived next door to their parents and siblings, which helped cousins stay close to one another and sometimes intermarry.

Some schedules may have data on the last image of the record set or roll. If a household was skipped (when the residents were not home), the enumerator made a note and wrote the information on the last page. Many of the records I have seen for 1950 have had this occur when more women worked outside the home.

Census records can be a huge help in telling that family story. Compare the address listed with maps that were from that time frame to check the nearby schools, businesses and other historic places. Contact me if you need help using historic maps as that aspect of genealogy research is one of my favorites! Enjoy solving mysteries using these records!

Image reference:

Census Records. USA. San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas. 1 April 1950. McNeal (McNeil), Clyde. ED 265-67. Roll 1602. p. 14. https://www.ancestry.com/ : accessed 20 August 2022.